And if you go chasing rabbits

And you know you’re going to fall ...

— Jefferson Airplane, “White Rabbit”

One hundred years after Alice’s bad trip in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), Jefferson Airplane cooked up their psychedelic classic “White Rabbit”. The song is an acidic tribute to altered consciousness, equal parts prescription and cautionary tale, named for the anxious being Alice glimpses in the opening paragraphs of Carroll’s book:

So she was considering in her own mind (as well as she could, for the

day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether the pleasure of

making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and

picking the daisies, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

Alice’s condition is familiar to most writers: sure, it’s pleasing to string words together, but getting started can be real trouble. Sometimes a freaky rabbit has to intervene. In Alice’s case, as almost everyone knows, the intervention of the White Rabbit sends the girl’s sleepy mind on a lunatic journey. “Down the Rabbit Hole”, the title of Carroll’s first chapter, has become synonymous with radical departures of thought and experience, as in the 1999 film The Matrix, where a drastically revised perception of reality is expressed as “tumbling down the rabbit hole.”

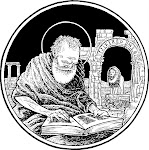

As a representative of wild inspiration, it’s tempting to induct the White Rabbit into the Writer’s Pantheon. But he’s preoccupied by a pocketwatch, not a writing desk, and besides, another Rabbit takes precedence in our literary assembly, thanks to an image on Mayan pottery that predates Alice by at least 1000 years. A vase discovered in northern Guatemala depicts a scribe, a familiar and pervasive figure in Mayan culture, though in this case the depiction has no known counterpart in surviving Mayan art: the scribe is an anthropomorphic Rabbit, dutifully taking notes as a court’s chaotic business is transacted around him, including, it seems, a human sacrifice. The artefact probably is a funerary vase (folks with stronger stomachs have speculated the vessel was used for drinking chocolate) and the scene likely is a legendary depiction of the underworld (we’re down the rabbit hole again), a realm where the scribe clearly maintained a lofty and highly ritualized position as a mediator between the bloodthirsty transactions of humanity and the inconceivable business of the gods.

Generally the scribe in Mayan art was depicted in human form, and the primary scribe-deities were Itzamna (the creator god, inventor of writing), or Pauahtuns (an individual or group of gods associated with scribes and artisans), or a pair of anthropomorphic howler monkeys (gods of the Mayan arts, including writing and sculpting). These members of the Writer’s Pantheon will be given reverent attention in due course. As for our scribe-Rabbit, his potential to inspire tangents of creativity is supported by the characteristics of rabbit or hare divinities of other cultures, where this creature often serves as a trickster, a prolific creator, a bringer of luck, a messenger, and, in the case of the Aztec’s four-hundred rabbit gods, a figure of drunken revelry.

However, this party animal obviously has a dark side. Let’s not forget the moral of Aesop’s fable of the Tortoise and the Hare: “A naturally gifted man, through lack of application, is often beaten by a plodder.” Beware of pride and procrastination, you harebrained writers! A number of cultures associate rabbits and hares with the moon, vacillation, and fear, and as is the case with the White Rabbit and his Mayan counterpart, dreadful access to the underworld. In one of my favourite books, Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883), there is a wonderfully surreal scene in which Pinocchio stubbornly refuses to take his medicine, at which point four ink-black rabbits arrive, carrying a coffin, ready to transport the puppet to his grave. Pinocchio is horrified into taking his medicine, and the frustrated rabbits grumble about making their trip for nothing, though they imply they’ll have other opportunities to return and complete their grim business. Another favourite is David Lynch’s Rabbits (2002), a series of short films featuring “a nameless city deluged by a continuous rain [where] three rabbits live with a fearful mystery”. Later incorporated into Lynch’s feature film Inland Empire (2006), these anthropomorphic rabbits seem to be incarnations of doomed souls, struggling to recall (or perhaps to forget) how they ended up in such a miserable and transformed condition.

So is Rabbit good news or bad news for writers? If you’re looking for unrestrained creativity, enigmatic individuality, or obscure and eccentric tunnels into perception and expression, then say your prayers, because this is your patron. Proper invocation includes a dose of Jefferson Airplane. But keep in mind: Rabbit may lead you down routes that become curiouser and curiouser. Expect the unexpected, otherwise you risk losing your head. Go ask Alice, I think she’ll know.

Sources

“About the Rabbit” Anthrobytes Consulting

http://www.anthrobytes.com/rabbit.html (accessed 28 December 2008)

“Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll” Project Gutenberg

http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/19033 (accessed 22 December 2008)

“The Construction of the Codex In Classic- and Postclassic-Period Maya Civilization” Thomas J. Tobin.

http://www.mathcs.duq.edu/~tobin/maya/ (accessed 28 December 2008)

Dictionary of Symbolism. Hans Biedermann. Trans. James Hulbert. New York: Facts On File, 1992.

Fables of Aesop. Translated by S. A. Handford. London: Penguin Books, 1964.

“Great Rabbit / Hare”

http://community-2.webtv.net/TheObsidianMask/GreatHare/index.html (accessed 22 December 2008)

“Rabbit” Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabbit (accessed 22 December 2008)

“Rabbits (film)” Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rabbits_(film) (accessed 28 December 2008)

“The Rabbit Scribe” Ancienscripts.com

http://www.ancientscripts.com/rabbit.html (accessed 28 December 2008)

“The similarities between the ‘Rabbit-Gods’ The Great Hare, the Jade Rabbit and Wn” History of Rabbit Gods

http://www.geocities.com/TimesSquare/Labyrinth/6100/hist.html (accessed 21 December 2008)

“White Rabbit (song)” Wikipedia

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/White_Rabbit_(song) (accessed 24 December 2008)